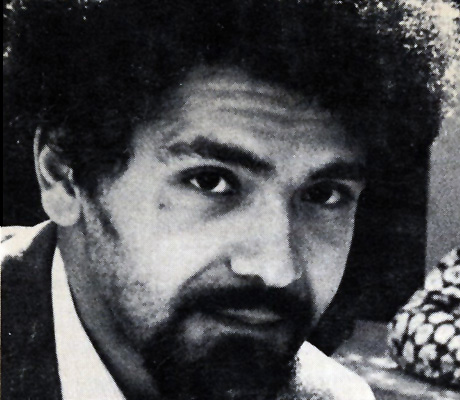

Lives of the Poets: Sotère Torregian

Sotère Torregian, a self-identified French surrealist, perhaps the only such macédoine extant in North America today, grew up in “No Man’s Land with lots of machine gun bullets flying all over the place,” a place known also as Newark, New Jersey, where he was born in 1941. He lived in a multilingual home where he learned French, Italian, Greek, and Arabic, among other languages. Identifying at an early age with the Africanized Mediterranean, he learned English with difficulty. He received instruction in handwriting and manners at St. Anne’s School in Newark, where he was expelled for kicking a nun.

Over the years of his youth he invented himself as a poet, attending readings at New York’s Café Le Metro with Paul Blackburn, Joseph Ceravolo, and David Shapiro and publishing his first poems with Art and Literature (Isere, France), Paris Review, and Ted Berrigan’s magazine “C.” He left the East Coast for California in the late 1960s and taught in the nascent African-American Studies program at Stanford. Since then he has published a half dozen books of poetry, including The Golden Palomino Bites the Clock (Angel Hair, 1967), The Age of Gold (Kulchur, 1976), and the one I published with Hoa Nguyen: “I Must Go” (She Said) “Because My Pizza’s Cold” (Skanky Possum, 2002). Punch Press recently published his latest collection, Envoy.

His father, a Cuban boxer, left the family when Torregian was twelve, but his rich family heritage helped the boy identify with intersecting cultural influences from an early age. “My grandmother,” he said in a recent conversation, “told stories about playing near the acropolis in the plain of Etna in Sicily.” The first story he remembers tells of a girl abducted by the devil in a town next to where his grandmother had lived. “It turns out to be the story of Persephone,” he said, “and of how she disobeyed her mother and went to pick flowers. Out of the earth the devil appeared and abducted her. So this is the story I was told until I was five. That was the intro to my ancestors’ sense of poetry.” This sense of poetry as the integrated and still-living myths of a people informed Torregian’s poetic affinities—affinities cooked up in the ethnically diverse and often dangerous Newark neighborhoods of his youth.

While attending public schools, Torregian experienced his first taste of racism and the uncomfortable disassociation this can cause. White kids often attacked him because of his mixed African ancestry, while blacks, confused by his identification with Mediterranean cultural traditions, targeted him for trying to pass as white. He took refuge in the library to escape these displays of ethnic hostility. Compelled by his alienation from North American racial roles and performative expectations, he pursued through careful study the traditions and stories bestowed on him at home. But despite his studious nature, he “failed” at poetry, so he says, “for not writing in iambic pentameter. [As happened to] Rimbaud, my teachers claimed I was a dunce.”

Perhaps an astrological accident in the house of Cancer preserved Torregian for the muses, despite his teacher’s claim of early poetic failure. Sharing a birthday with one of the great poets of the Negritude movement—Aimé Césaire—Torregian early on identified with the Martinique native. Through such associations, Torregian imagines an interpenetrating world of forms, where personal identification registers across ethnic and racial lines to correspond more intriguingly with dispositions of the soul. His identification with the French surrealist poets also led him toward a path where personal vision, intellectual pursuit, and international movements of art crossed personal boundaries to create a broad and influential current of artistic activity. As this was inflected through Torregian’s imagination, he was able to enter a community of fellow authors, and such imaginative, if hermetic, participation prepared him for his introduction, in the 1960s, to the New York School of poets.

In those days many poets congregated at the café Le Metro coffee house on the Lower East Side. There, Torregian met Paul Blackburn and Ted Berrigan, who, he says, taught him more than anybody else. “Ted one day was walking with me,” he recalls, “and he said, ‘Sotère, you’re a great poet but you have one problem: you’re too serious. I love your work, but you’re too serious.’” According to Torregian, “this changed everything. The French,” he continued, “were talking about the pain of love. Ted said, ‘You’ve got to get out of that. Put some laughter in your writing.’ The absurd became more important.”

A sense of the absurd has since permeated Torregian’s writing, and it connects most closely to his understanding of French surrealism. But also, recalls Torregian, the sense of adventure in Eugène Ionesco’s plays taught him to delight in the experience of the imagination. As he remembers it, Ionesco once said: “Any play that I write is an adventure, it’s a kind of a hunt, the discovery of a universe that reveals itself to me at the presence of which I am the first to be astounded.”

This feeling of adventure keeps Torregian’s ear alert to possibilities, and his poetry often moves at dazzling speed, connecting absurd but astonishingly concrete imagery that challenges a reader’s expectations of the poem. Anne Waldman has called Torregian “one of our most radically original poets.” She goes on to say that “his surreal lyricism, wild sense perceptions, strange imagery, and playful emotional trajectories are unique in contemporary poetry.” At turns also politically motivated, socially conscious, and mysteriously delighted by the correspondences of history and geography at play in popular culture, Torregian’s poetry charms for its generous, open-armed embrace of seemingly distant associations. For instance, “Come Back Africa” (1970) puts African American cultural history in conversation with the particular personal history of the poet. In part, it reads:

... there’s magic in whatever a Black Man touches

the railway the masses the drums of the Metro

Satan’s chimneys unloading everyday their dromedaries

in seraglio—

pajamas who step in leaps and boundsThese are

more than just

moteefs to be dealt with in the film and “integrated” into a poem:

a. children’s tin band playing

b. Makeba.

c. wife’s murder (?)

d. hero’s enemy¡Xotho is the language of hell where one must always

refill the bottles of hooch stolen from

the closets with water

that will not kiss you unless you give it five dollarsUnless you first spit

before you enter the door

Zululand of my soul you come to meet your Father

Dance playing the white goats as sousaphones

A more recent, unpublished poem, “The Price of Gold (Again) on the Market Today at $754.10,” considers the relationships of value between “civilization” and the historical and economic hardship of mining in geographically remote locations. He writes:

It isn’t Suzanne Pratt who announces it this time

but Suzie Gharib (Beauty takes the acrid taste

from ill-gotten gain) ebony torsos of miners

swathed

in sweat somewhere in Nelson Mandela’s homeland(Etruscan Minoan Assyrian Egyptian) Here I might be found

strumming a mandolin or perhaps caressing a mannequin’s nakedness“the on-line world getting even more crowded” Alors

avancer transporter esclaves à l’intérieure on the way

to Malebolge then Sol escudos corazon jaguar vasija

— O royaume! My Hetáirae passetemps in the

ellipse

Both poems infuse the everyday with a sense of historical continuity, cultural narratives interweaving in the play of poetic art. The “surreal” experience of the poem exists insofar as distinct cultural formations are associated in close range of the poet’s sense of delight and curiosity. Torregian’s artistic affinities are integrated with an understanding of the coexistence of diverse phenomena that only poetry can bring into awareness through careful (and playful) association. The powerful and unassuming voices he provides to readers are, indeed, undercut with a profound sense of the absurd. And yet, such absurdity comes not so much from the poem as from the complex weave of contemporary life and attention to it.

It is not difficult to imagine how the life of a French surrealist in North America can be hard to sustain. In efforts to support his writing over the years Torregian has worked at a number of jobs, notably contributing to the development of the aforementioned African American Studies program at Stanford in the 1960s and ’70s with anthropologist St. Clair Drake. He bonded with Drake over their connection to the Négritude poets, and as a result of his studies in African cultures, Torregian was invited to present lectures on African literature and philosophy. He worked with Drake until 1975, when Drake retired and Torregian’s position was eliminated during a highly sensitive political moment. He found employment in Menlo Park public libraries until the death of his mother triggered agoraphobia. For many years he could not leave his house, forcing him to live primarily on SSI disability.

Over the years that I have corresponded with Torregian, first in the Bay Area and now at his home in Stockton, California, I have been grateful for the view of the world he has maintained, for it is deeply humane and learned. And his humor slices through the darker realities of his life, which include poverty, racial adversity, and isolation. He has moved several times since I’ve known him, landing in Stockton several years ago. There he endures the Central Valley’s long summers. He survives on very little, sharing an apartment with his cats. But I remember how we once met in San Francisco soon after Fred Rogers, the creator of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, had passed away. Torregian expressed sincere sadness, recalling how his children had grown up entranced by the educator’s public persona. Listening to Torregian’s recollections led me to reflect on my own experience of childhood, and turned my attention to Mr. Rogers with great sympathy.

In this way Torregian can spin the world without the glaze of irony. This is perhaps what is most surreal about him: he embraces the full force of things with a curiosity and a sincere persistence that helps increase perspectives of the truly strange cultural carnivals of celebrity and loneliness, public action and private pain. While he is a man (like many) who has devoted a life to poetry for little monetary return (his few awards include the Frank O’Hara Award for Poetry in 1968), his evaluations of popular culture, contemporary politics, and social policy, along with a rich, Euro-American poetic tradition, contribute an extraordinary vision. His compulsive devotion to the art of writing proposes an intensity of purpose that evades easy categorization. He is in the world on his own terms, yet we gain as readers by his perseverance in them.

Dale Smith has published essays, reviews, poetry, and criticism, most recently Slow Poetry in America (Cuneiform, 2014) and Poets Beyond the Barricade: Rhetoric, Citizenship, and Dissent after 1960 (Alabama, 2012). He earned a PhD in rhetoric from the University of Texas at Austin and teaches English at Toronto Metropolitan University....

-

Related Authors

- See All Related Content

Dale, you've done a great service to poetry in this essay. Torregian, gifted

and courageous, is an exemplary poet.

Edward Mycue